Closure

Callback, Closure

So we know functions are first-class citizens in JavaScript. While studying first-class function we heard a term callback. Today we will learn what are callbacks and closure and what is their use.

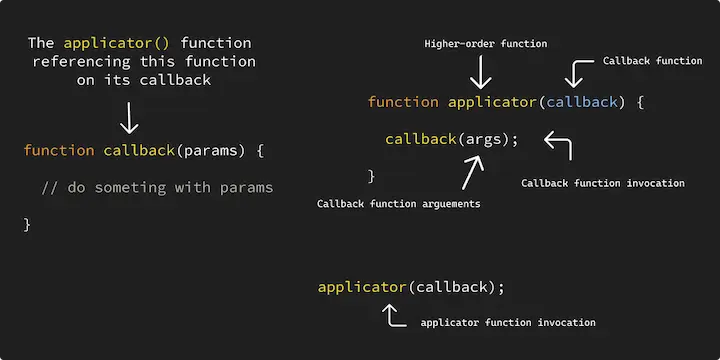

What is a callback?

Any function that is passed as an argument is called a callback function.

A callback is a function that is to be executed after another function has finished executing - Hence the name callback.

In JavaScript, functions are objects. Because of this, functions can take functions as arguments and can be returned by other functions. Functions that do this are known as a higher-order functions.

Callbacks are used in two ways:

- Synchronous

- Asynchronous

Synchronous callback functions

If the code executes sequentially from top to bottom or order by order, it is known as synchronous.

Let's take an example:

console.log(1);

console.log(2);

console.log(3);

output:

1

2

3

Let's take another example:

console.log(1);

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(2);

}, 1000);

console.log(3);

output:

1

3

2

In the first example, the output was 1,2,3 but in the second example, it produce 1,3,2 why?

There is nothing wrong with the code, the JavaScript engine executes the code in the correct order. JavaScript is a single-threaded synchronous programming language. It waits for none. Hence, it queued the console.log(2) in the last because it wrapped inside the setTimeout() function which is ordered to execute 1000ms later. Thus, the JavaScript engine queued the code like this:

console.log(1);

console.log(3);

console.log(2);

So, now we understand what is Synchronicity. Let me take an example of the Synchronous callback function.

function greetPeople(array, callback) {

array.map(callback);

}

function greet(people) {

console.log(`Hello, ${people}`);

}

let peoples = ["Biswarup", "Satish", "Akshay", "Hitesh"];

greetPeople(peoples, greet);

output:

Hello, Biswarup

Hello, Satish

Hello, Akshay

Hello, Hitesh

In the above example, the JavaScript engine did not wait for the .map() function to finish first and then execute greet(). Rather, geet() function is executed in each iteration. Here, the greet() function is an example of a Synchronous callback function.

Asynchronous callback functions

Asynchronous means that if the JavaScript Engine has to wait for an operation to execute. It will execute the rest of the code while waiting.

tip

JavaScript is a single-threaded programming language. It carries asynchronous operations via callback queue and event loop.

Let's take an example: Suppose we need to code a program, where we will download a file. After finishing the download, it will open.

For downloading a file it takes time, let's say it takes 5s to download.

function downlaod(file) {

let fileName;

console.log(`downloading ${file}...`);

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(`${file} downloaded.`);

fileName = "file.pdf";

}, 5 * 1000);

return { fileName };

}

function openFile(fileName) {

console.log(`opening ${fileName}`);

}

const file = `https://abc.xyz/file.pdf`;

const { fileName } = downlaod(file);

openFile(fileName);

output:

downloading https://abc.xyz/file.pdf...

opening undefined

https://abc.xyz/file.pdf downloaded.

The JavaScript engine finished executing the code, but it did not execute the code as we expected. The program tries to open the file before it is downloaded. We know why this happens, because of the synchronous nature of JavaScript. It waits for none.

To make the programme correct we need to implement a callback. In our example, the openFile() function should execute after the file has finished downloading.

Let's refactor the code:

function downlaod(file, callback) {

let fileName;

console.log(`downloading ${file}...`);

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(`${file} downloaded.`);

fileName = "file.pdf";

callback(fileName);

}, 5 * 1000);

return { fileName };

}

function openFile(fileName) {

console.log(`opening ${fileName}`);

}

const file = `https://abc.xyz/file.pdf`;

downlaod(file, openFile);

output:

downloading https://abc.xyz/file.pdf...

https://abc.xyz/file.pdf downloaded.

opening file.pdf

Now, the program works exactly we expected. In the above example openFile() is an example of an Asynchronous callback function.

Hope you get the idea of callback functions.

Summary

Any function that is passed as an argument is a callback function.

Callback functions can be Synchronous or Asynchronous

Closure

Let's go back to the day 5 and 6: We studied the function scope. Where we learned we cannot access variables declared on other functions unless it is lexically bounded.

let's take an example: If we try to access a variable declared on another function we will get a ReferenceError.

function sayHello() {

let message = "Hello";

console.log(message);

}

function greetMe(person) {

console.log(`${message}, ${person}`);

}

sayHello();

greetMe("Biswarup");

As expected, the JavaScript engined returned a ReferenceError: message is not defined.

But in the below example, it did not return any error.

function downlaod(file, callback) {

let fileName;

console.log(`downloading ${file}...`);

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(`${file} downloaded.`);

fileName = "file.pdf";

callback(fileName);

}, 5 * 1000);

return { fileName };

}

function openFile(fileName) {

console.log(`opening ${fileName}`);

}

const file = `https://abc.xyz/file.pdf`;

downlaod(file, openFile);

The openFile() function can access the variable fileName declared in another function download(). According to the function scope, it should not be happed right? Yes, it should not.

Pay attention to the download() function it recieves a callback function openFile() or in other words openFile() function is nested inside the download() function.

From the lexical scope, we learned that if a function is nested inside a function. The inner function has access to the outer function scope. Meaning, the most inner function can access the variable from the outer functions. That's why openFile() function has access to the download() function.

We get the idea now let's fix the sayHello() example.

function sayHello(callback, person) {

let message = "Hello";

callback(person, message);

}

function greet(person, message) {

console.log(`${message}, ${person}`);

}

sayHello(greet, "Biswarup");

sayHello(greet, "Akshay");

output:

Hello, Biswarup

Hello, Akshay

Now let's modify the code using partial functions:

function sayHello(callback, message) {

return function (person) {

return callback(person, message);

};

}

function greet(person, message) {

return `${message}, ${person}`;

}

const greetingHello = sayHello(greet, "Hello");

const greetingHi = sayHello(greet, "Hi");

const greetToBiswarup = greetingHello("Biswarup");

const greetToAkashay = greetingHello("Akshay");

const greetHiToBiswarup = greetingHi("Biswarup");

const greetHiToAkshay = greetingHi("Akashy");

console.log(greetToBiswarup);

console.log(greetToAkashay);

console.log(greetHiToBiswarup);

console.log(greetHiToAkshay);

output:

Hello, Biswarup

Hello, Akshay

Hi, Biswarup

Hi, Akashy

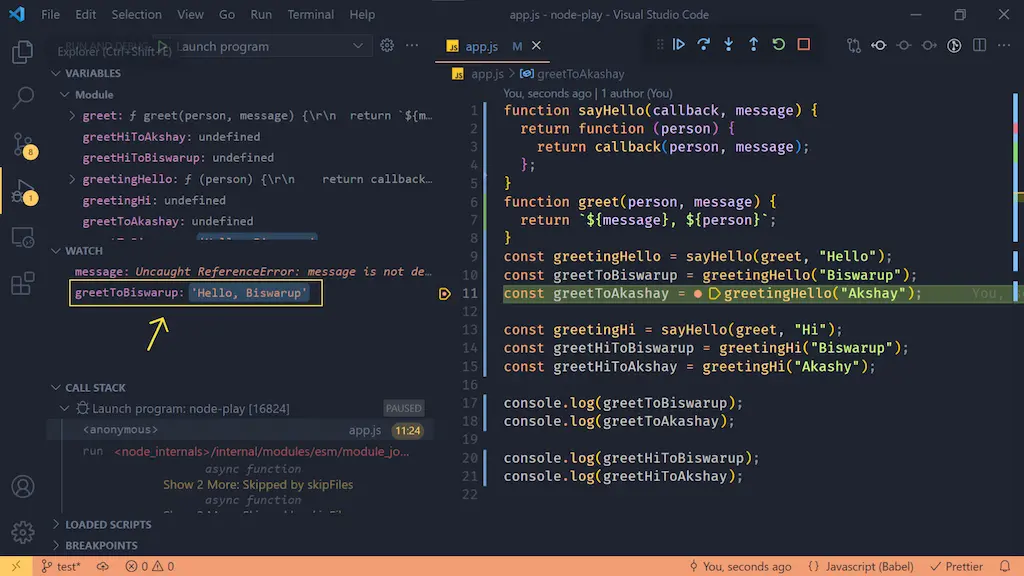

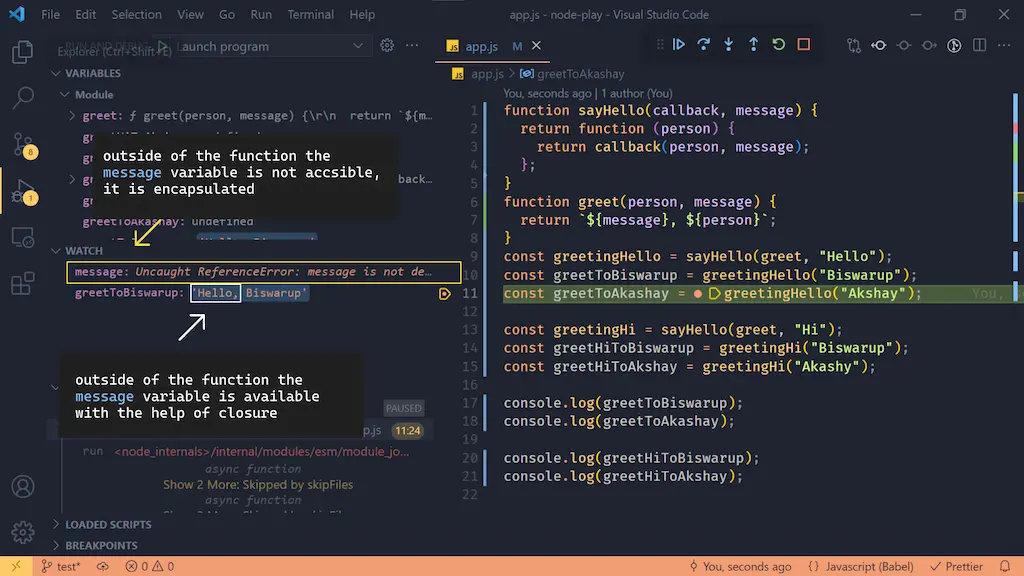

Now let me show you an interesting thing, I stop the execution right after the greetingHello("Biswarup") function has finished executing. At this point, if we watch the greeetToBiswarup variable is assigned a value with Hello, Biswarup. Till now everything looks good. Do you remember how this variable is assigned? Yes, the value assigned by the greet() function, alright. So the value is a combination of person and message variables right? Yes, thus it returned Hello, Biswarup.

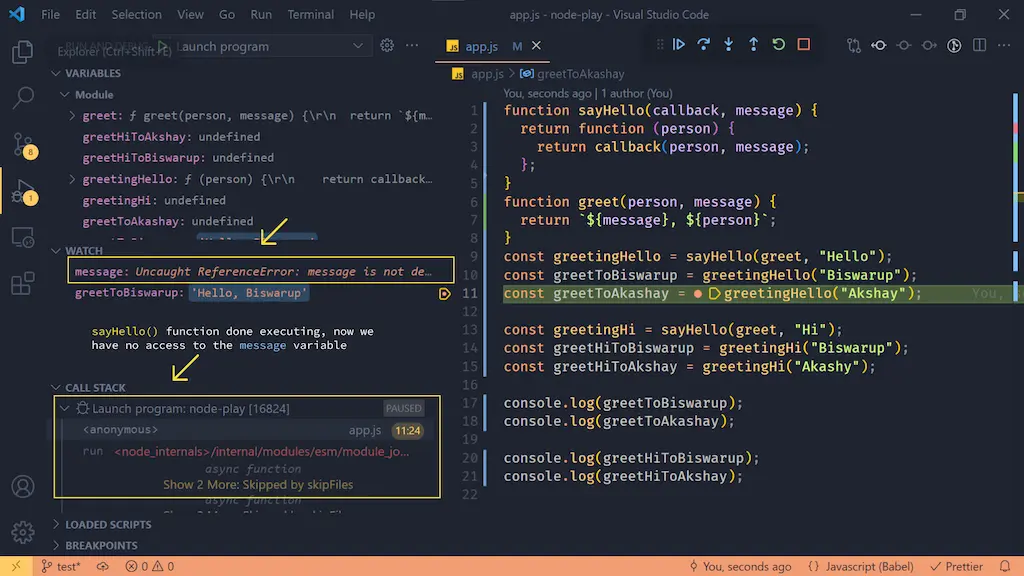

Normally, a local variable only exists during the execution of the function. The sayHello() function has done executing, it was contained with a local variable message. Now the sayHello() function is not the call stack, we have no longer access to the message variable, very good!

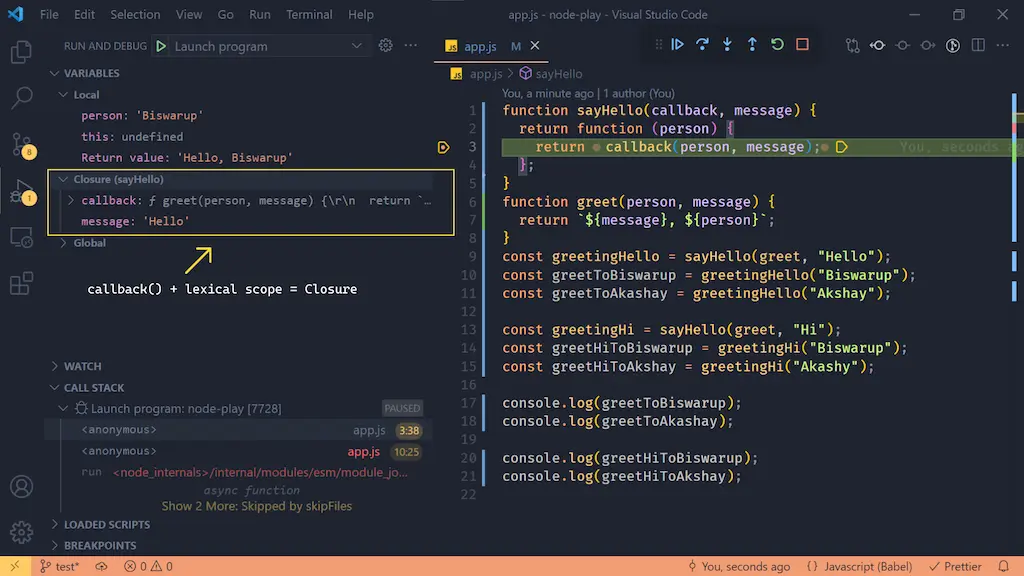

Here is the fun part, still have access to the message variable. Let me remind you, the variable greetToBiswarup is a combination of the message and person variable right? And we have no longer access to these variables, right? But greetToBiswarup contains the value of the above variables. How? this happened because the callback function and the lexical scope together formed a closure.

Let me explain, the greet() function is nested inside the sayHello() function. The sayHello() function receives two arguments a callback function and a variable. The callback function is nested inside the sayHello() function which is lexically bunded by the sayHello() function, meaning the callback function has access, to the sayHello() function's scope. At the same time the callback function is referencing to the greet() function, meaning the greet() function has access to the sayHello() function's scope. That's how the greetingHello() gain access to the message variable. But we cannot directly access the message variable. The greetingHello() function has access to the message variable because of the closure.

What is closure?

A closure is a combination of a function bundled together (enclosed) with references to its surrounding state (the lexical environment). In other words, a closure gives you access to an outer function's scope from an inner function.

Advantages of closures

By using a closure we can have private variables that are available even after the function has finished its execution.

With a closure, we can store data in a separate scope and share it only where necessary. In other words, with closure, we can achieve data encapsulation.

In the above example, the message variable is encapsulated. It cannot be accessed by the outer world. However, its value is available to the outer world.